Learning about the first animals from life at the poles

The amazing survival strategies of polar marine creatures might help to explain how the first animals on Earth could have evolved earlier than the oldest fossils suggest according to new research. These first, simple and now extinct, animals might have lived through some of the most extreme, cold and icy periods the world has ever seen. The study is published in the journal Global Change Biology, published this week (12 October 2022).

The fossil record places the earliest animal life on Earth at 572–602 million years ago, just as the world came out of a huge ice age, whilst molecular studies suggest an earlier origin, up to 850 million years ago. If correct, this means that animals must have survived during a time influenced by multiple global ice ages, when the whole or large parts of the planet were encased in ice (snowball and slushball Earths), far bigger than any seen since. If animal life did arise before, or during, these extreme glacial periods it would have faced conditions like modern marine habitats found in Antarctica and the Arctic today, and required similar survival strategies.

Over millions of years, the expansion and contraction of the ice sheets during cold and warm periods has driven the evolution of Antarctica’s thousands of unique animals and plant species. The same could be true for the evolution of animal life on Earth. Whilst to humans the polar regions seem like the most hostile environments to life, they are the perfect place to study the past and the potential for life in the universe beyond our planet, such as on icy moons like Europa.

Marine biologist and lead author, Dr Huw Griffiths of British Antarctic Survey (BAS), says:

“This work highlights how some animals in the polar regions are incredibly adapted to life in and around the ice, and how much they can teach us about the evolution and survival of life in the past or even on other planets.

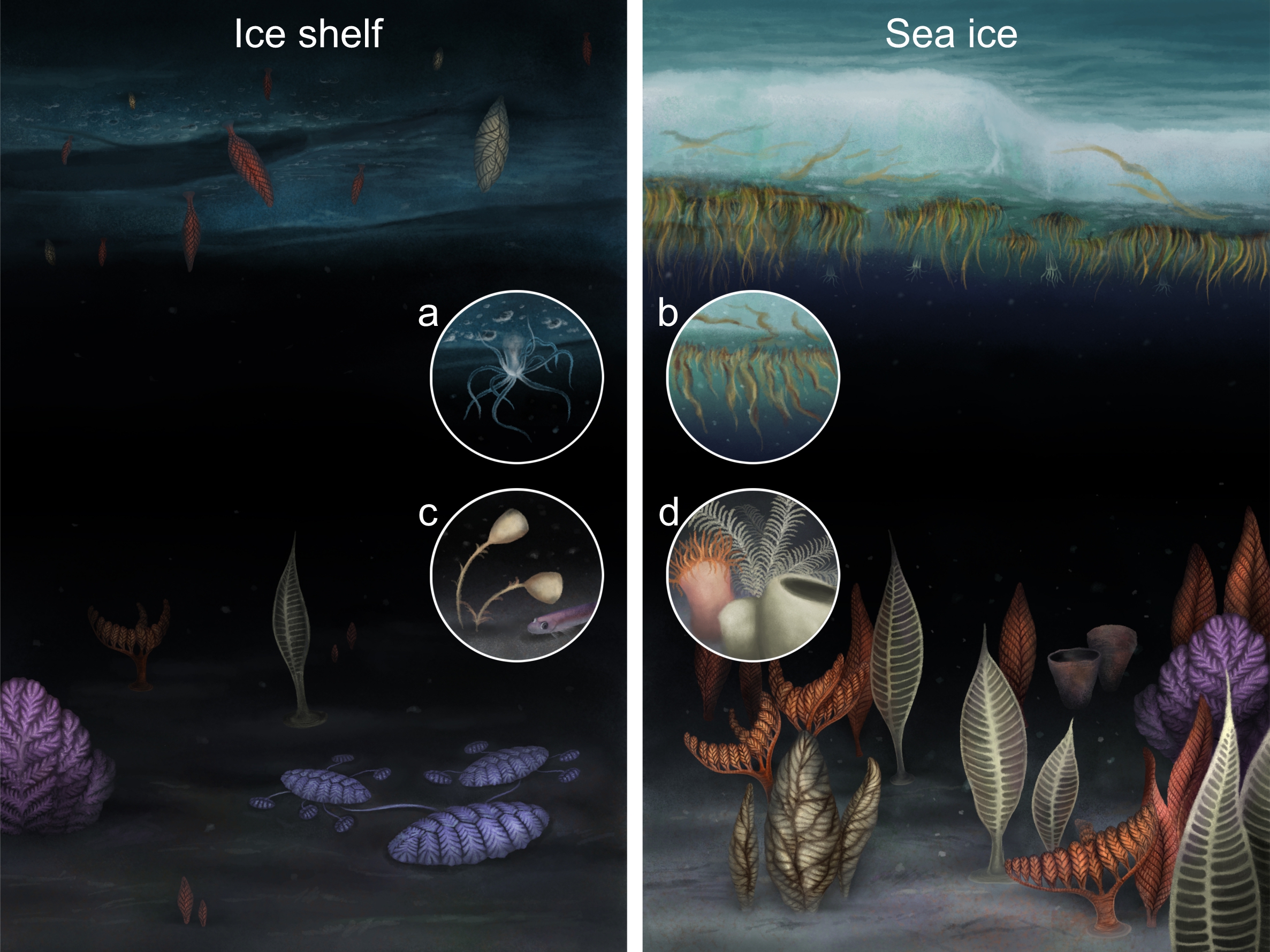

“Whether it is animals living upside down on the underside of ice instead of the seafloor, sponges living hundreds of kilometres under thick floating ice shelves, organisms that are adapted to live in seawater colder than −2°C, or whole communities existing in the darkness on food sources that don’t require sunlight, Antarctic and Arctic life thrives in conditions that would kill humans and most other animals. But these cold and icy conditions help to drive ocean circulation, carry oxygen into the ocean depths and make these places more suitable for life.”

Floating ice covers more than 19 million km2 of the seas around Antarctica and 15 million km2 of the Arctic Ocean during winter. Under possibly the most extreme snowball Earth, lasting 50 to 60 million years during the Cryogenian period (720 to 635 million years ago), the whole world (510 million km²) is believed to have been entombed in ice around a kilometre thick, but there is some evidence that this ice was thin enough at the equator to allow marine algae to survive.

“The fact that there is this huge difference in the timing of the dawn of animal life between the known fossil record and molecular clocks means that there are huge uncertainties about how and where animals evolved” says co-author Dr Emily Mitchell, palaeontologist and ecologist at the University of Cambridge. “But if animals did evolve before or during these global ice ages, they would have to contend with extreme environmental pressures, but ones that may have helped to force life to become more complex to survive.”

“Just like in Antarctica during the Last Glacial Maximum (33-14 thousand years ago), the huge amounts of advancing ice would have bulldozed the shallows, making them inhospitable to life, destroying fossil evidence and forcing creatures into the deep sea. This makes the chances of finding fossils from these times less likely and sheltered areas and the deep sea the safest places for life to evolve.”

Dr Rowan Whittle, polar palaeontologist at BAS and co-author on the study says:

“Palaeontologists often look to the past to tell us how future climate change might look, but in this case we were looking to the coldest and most extreme habitats on the planet to help us understand the conditions that the first animals might have faced, and how modern polar creatures thrive under these extremes.”

Animal survival strategies in Neoproterozoic ice worlds by Huw J. Griffiths1*, Emily G. Mitchell2 and Rowan J. Whittle1 is published in the journal Global Change Biology: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gcb.16393